The Catch Newsletter

April 2022

Welcome to Talon Review’s April 2022 edition of The Catch newsletter! This month’s feature is a transcribed interview with poet & author Ira Sunkrungruang, followed by an artist feature from Luc Napier, and a small announcement from the Talon Review team.

Book Interview: This Jade World - Ira Sunkrungruang

Interview by Kail Anderson and Natasha Kane

Transcription by Natasha Kane

THE FOLLOWING IS A TRANSCRIPT OF AN INTERVIEW. Kail AndersoN (eDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF THE tALON rEVIEW) and Natasha Kane (lEAD eDITOR OF THE cATCH) INTERVIEWED iRA sUNKRUNGRUANG, THE AUTHOR OF tHIS jADE wORLD, ON oCTOBER 25, 2021.

Natasha: I’m curious about jade. My mom and my grandma are actually from Thailand as well, so when I think of Thailand, I think of the lotus flowers that you actually mentioned early on in the book. I’m curious about what drew you towards jade.

Ira: Well, I’ve always been very fascinated with the color green. Especially the color green in Thailand. I always used to compare central Thailand to the geography of the mid-west and the flat of Illinois or even the flat of Florida. Then around five years ago, it was the first time I really looked at the flat of Thailand, and it’s actually nothing like the other flats! There’s nothing like the green that exists in Thailand. My father would say, “This is jade, we live in a jade world.” It’s a green that is breathing, it’s a green that is living. It’s also a green that hides, but a green that is somewhat transparent if you want to look through it. My father described the green in such a way that expressed the love he had for the flat of Thailand. This Jade World became part of an examination of landscape because I think growing up as an immigrant son, I was told by my mom and dad “Thailand is a home.” But I lived in America and visited Thailand every other year, so that idea didn’t really sink in. It wasn’t until later in my life that the idea started to sink in. In northern Thailand, where my mom and her sisters lived, there’s an order that this wonderful little jade trade. One of the chapters is about going to find a little jade ring for my then-partner, which has kind of made its way into the book too. I think if you do like a lot of research into jade itself there’s this mystical, mythical quality about it. I’m really kind of enamored by the stone itself too. There’s so many variations of it. I think that’s how This Jade World came about. But lotuses for sure are a part of Thailand. I identify the lotus with my mother more than anything else. It is Thai but it’s more her because that’s her flower, she loves it so much.

Kail: Would you say there’s something hypnotic about the pace in Thailand, compared to America?

Ira: Yes! But it’s more than just pace. Living in a Buddhist country, a country with different values creates a rhythm too. A rhythm of understanding. I always say that every time I go to Thailand, it takes me a couple of days to adjust. It’s like a house but I feel like someone’s moved all of the light switches! It takes a bit of time but I think it’s because every time I go to Thailand, I’m always struck by a peaceful rush. It’s so populated. There’s so many people. There’s not an absence of sound. Things are happening all the time in Chang Mai and Bangkok, which is where I usually spend most of my time. But yet, at the same time, there’s this kind of slow easygoingness and I think that comes from the Buddhist culture. The whole country is deeply Buddhist, and they’re so chill. It’s a very chill atmosphere, a way of being that we don’t get here. There’s always this frantic pace. When I get to Thailand, things slow down in a way that I don’t really know what to do with myself for the first couple of days. And then I’m like “Oh, just be, just be present.”

Kail: I could really see that idea of pace in this book. Almost like you can feel how present the writing is, compared to the American mindset of “I need to achieve this next thing, I’m writing this stanza to get to the next stanza.” Whereas a lot of this book can hold itself. You can separate one chapter from everything else and it’s still a whole piece of work.

Ira: I love that. I love how you put it that way. This book really is a different type of memoir. It’s a memoir that isn’t strictly chronological. The book jumps around from time to time, but I like what you said. That there are these self-contained moments, these self-contained worlds in here. You see a narrator trying to be present and trying to figure out why he wasn’t present at times. I actually wrote the first draft of this book in Thailand, and I think I had to be in that mindset to have written this book. It made me more in tune with the things happening around me. I think I’d be too angsty if I wrote it here aha.

Kail: Yeah, it feels really vulnerable in that sense. That you needed to be in that one specific place or timeline.

Ira: Definitely. This was written in six weeks, during one trip. It was very meditative.

Natasha: Staying on the theme of vulnerability, a lot of the book focuses on divorcing from your partner, who was also your mentor for a while. Would you say that there’s a grieving process that one has to go through with not only losing a partner but; also, grieving the person that they became with their partner?

Ira: That’s a really awesome question. See, I think the book is about not knowing who you are after being with someone for so long. Especially someone who, as you mentioned, acted almost like a mentor in many ways in the world. I don’t know if it’s grieving the person. I think it’s more of understanding the evolution of who you are. That person doesn’t really die or go away. I think this is something the book is trying to reconcile. That these things that happened in his childhood, with his parents and their divorce, those things are still ever-present in him now. So, really it becomes a reconciliation of the multiple people that you are as you evolve through life. Instead of it being a grievance of your former self, I kind of feel like it’s a homage to your former self. They were essential for you to get to where you are now. That’s the reason I love nonfiction so much. I don’t believe in time so much, which is why I think I wrote this book in this way. I think the only area where time has meaning is the “I” that is always evolving. You’re always changing from one moment to another. Does that mean that this book is not true anymore because I’m a different person right now? Absolutely not. It’s just true to the person I was when I wrote it. It’s a true marker of who I was then. I went into the writing of this not trying to grieve the person I was, but I think I was trying to understand who I was. I was trying to figure out what I am now and what I want now. It’s more of a search for that. Even with the grievance of a relationship, our relationship had evolved too. It’s a different relationship now, it’s a better relationship. I think one of the things I’m always fighting against is this idea of writing too close because I don’t really think there’s such a thing as closure for this. I believe in movement, evolution, and understanding. Those things are ever fluid.

Kail: I feel like we have similar feelings about time. I think you can almost transverse time. You’re existing somewhere but you’re almost somewhere else at the same time. I feel like your book captures that. In one moment, you feel like an adult and in the next, you feel like a kid. It’s like that transparency of jade, like real jade being transparent. Wow. I was just making those comparisons on the fly, but it turned into a gorgeous comparison. Haha!

Ira: No! That’s so good! I love what you said there. What’s really interesting, and how you say that we’re traversing time, is that memory is something we can’t live. Memory is timeless and memory doesn’t have logic. Part of the joy of being human is memory. What memory can do and why a memory suddenly happens. You’re trying to figure that stuff out. For instance, you’re sitting in a class and suddenly you are 8 years old again. You don’t know why you’re 8 years old again. You’re just sitting in class and it’s something that just happened. I think for me, it’s the interrogation of the memory that is deeply satisfying too. Not trying to rationalize it because that would be an impossible task, but trying to figure out “Why is it that I’m here right now?” I also believe that our memories present a truer self than who we really are. In This Jade World, I feel like the person that I was, who was going through a divorce, was not really present. He threw himself into work so that he could avoid. When someone asked how he was, he would say, “Fine. I’m fine. I’m good, thank you.” But inside, in that interior life, he was everywhere. He was moving in different directions. I think the joy and difficulty of writing this book was to find an order, to find out how to put these moments together. It’s one thing to say, “I love fragmentation; I don’t believe in time.” However, at the same time, you’re writing to readers who need some sense of order. You can’t give too much fragmentation. If you give too much fragmentation, readers are lost in the woods and they don’t know how to get out. Part of writing is looking at your memory, looking at the illogical movements of your memory, and coming up with some sort of guidance. Some sort of narrative pull or engine that gets us somewhere. Another thing I believe in is that when we go into a book, we see a character in one way, we have to expect them to be a different character when we leave the book. So, that is another kind of way of looking at how evolution or time matters. There’s still that expectation that he’s gonna come up. Well, in nonfiction it’s obvious. Like you wrote the book, of course, you’re in a different place! Ha! I think readers are searching for the how.

Kail: In that “how” do you feel that there’s hope? Do you feel like that’s what we as beings are clinging to?

Ira: In this book, yes. Hope is really important. Hope is what drives this book. The hope of finding another, loving again. That hope of being in a better place with yourself. Hope that these things are happening so better things can happen. I think a lot of this book is about trying to find that hope again. In the book, you find the character, or myself, in a state of hopelessness. Part of that year is to try to find what gives hope. Where does hope come from? Where can I draw hope from? One of the things that I don’t want the book to do, that is in a lot of “finding love” memoirs, is that it’s always another person that brings hope again. I think really the book is about the individual trying to find hope first. That’s more important because that means the person is shouldering the weight of trying to figure himself out. So, this hope is an internal hope. When we get to the end of the book, we get to this point where he realizes that there are things he hasn’t fully forgiven himself for. At the core of forgiveness is hope. Once you’re able to forgive, you’re able to imagine a different life.

Natasha: Going back to the beginning of the book, there’s the opening chapter titled “The First.” There’s a distinct lack of indentation. Was the lack of indentation tied to the idea of being present but, also; still not knowing yourself?

Ira: I’m a writer who really thinks about shape because I’m a poet too. I think when you’re a poet, shape is equally important, if not sometimes more important, than the language. Shape is a thing that announces to readers how you want them to read the poem. If a reader comes into a poem with a skinny shape, it’s showing a quicker pace and a quicker rhythm. I chose in the first chapter to include no indentation because I wanted to create a very claustrophobic feel. To really capture the uncomfortable overwhelming sensorial rush. In that particular chapter, some of the sentences are longer. They kind of repeat each other, they go back and forth. It plays with repetition. It’s overlapping because that’s how the person in that scene, in that motel, is feeling. It’s a mix-up, it’s a mess up, it’s a mess. I wanted to keep these emotions contained in the density of a paragraph. It’s a big risk when a writer chooses to do a long paragraph. Especially as the first movement of the work. I always ask my students, “What happens to you when you’re looking at a textbook and you see a long paragraph?” They always say, “Oh I zone out man, I’m out.” So, for me, I took a risk. But I really wanted to create that sense of being overwhelmed, of being lost. I think in terms of the lack of indentation, the lack of paragraphs, it really puts us inside the mindset of a person who is going to be with the first woman who is not his wife for the last 15 years. It’s uncomfortable. You can’t escape the confines of the paragraph.

Kail: You’ve mentioned how being a poet impacts your writing. In the chapter “It’s Raining,” you were referencing everyone as if they were stop lines of a poem. It seemed as if that was the poetry right there, unfolding in front of you.

Ira: When you decide to dedicate yourself to the art of poetry, your vision of life changes. Now, you’re concentrating on music or anti-music. I feel like life offers these moments of alliteration, a rolling alliteration. Where sound is just punctuated over and over again. Or, we get repetition. In that chapter, the repetition is of my mom saying, “It’s raining, it’s gonna rain, it looks like it’s gonna rain, it looks like it’s gonna rain.” That repetition becomes a way to talk about how uncomfortable the situation is. That’s why she keeps repeating to herself, “I don’t wanna be in this car, it’s uncomfortable, so-and-so is crying about her husband not treating her well, oh, it looks like it’s gonna rain!” It’s a repetition! It’s a poetic device of avoidance. I think it’s really great when you start combining craft with circumstance. Like what is actually happening in the life. Craft, this thing that the writer is doing that we call craft, is a representation of a larger thing about character, humanism, and vulnerability. You should go for metaphor, but you should go for metaphor because we’re always in metaphor. Like our lives are metaphor. We’re always trying to harken to something that’s lost, especially when we talk about memory. I think poetry does that. I think poetry forces you to look at the world from a lens that is very different from everyday being. Everything you see is a movement, it’s a pacing, it’s a tone. Then, you bring those things and put them into a poem.

Kail: On page 161, it states, “I think everything we do in this world is in search of identity.” I feel like I really gravitated towards this because everyone is sort of grasping for this concept of someplace to belong or someplace to be instead of just being.

Ira: Right. Absolutely. The more I think about literature and being a writer, I think literature almost comes down to two things. One is the search for who you are. The other one is searching for what you want. The issue of identity is probably the reason why a writer comes to the page in the first place. Even the romantics. who were waxing elegantly about pastures, they’re doing it because they wanna locate themselves. Wordsworth is trying to locate himself within this green. “Where am I?” “Who am I in this world?” That’s where you get transcendentalism. There’s this identity crisis that’s happening. But wanting (the other one I feel like most conflict in literature is about) is wanting. It’s about, “This is what I want, but this is what I have.” Right? The conflict would then be “Am I okay with what I have? Am I gonna be okay with never wanting or getting the thing I want?” In fiction, that could be no. They’re not gonna be okay and that’s where all hell breaks loose. In nonfiction, there’s a recognition of this is what I wanted, like I wanted a marriage to last forever, but this is what happened. What now? What do you want? Do you want change? To me, that is the core of most literature. What comes between identity and want? It’s always been my understanding that the two are linked.

Natasha: It’s so funny that you brought up Wordsworth because I’m currently in a class that only focuses on Wordsworth’s work. And I thought it was going to be painful, but I’m actually really finding enjoyment in his manipulation of pastoral conventions. During the era he lived in, pastoral conventions depicted the ideal life. There’s this idea of a peaceful shepherd and a peaceful life. After hearing your thoughts about identity and want, I’m wondering if Wordsworth’s inability to attain that ideal life led to his critique of it. Do you think that’s something that reflects in poetry for other poets? The desire for something and the inability to attain it leads a writer to criticize it.

Ira: Yes! That becomes the conflict. That becomes the reason why the poem exists. Like if Wordsworth was able to achieve exactly what he wanted, the poems would suck. There would be a lack of tension, a lack of urgency. I think the reason behind why we read poems and stories is because the writer has presented something that they’re deeply perplexed by. Something that deeply has them spinning and they’re trying to figure that stuff out. I think for sure, with Wordsworth, and A LOT of romantics, most of them have this idea of what the world should be and then they find out that it isn’t. That’s the reason they go to the page. So, absolutely. Everything would be too beautiful if Wordsworth had his way. There wouldn’t be anything at stake. All good literature has to have something at stake. You’re either going to lose something and never gain it back, or you’re gonna lose something and search for something else.

Kail: At one point in your book, you said you were afraid of losing everyone, everyone who ever loved you. There’s also this fear of losing your sense of self. Almost going into the woods and hibernating.

Ira: Yeah, that was a dark time. Ha. Yeah. Well, I mean part of the book is also part of this idea of mental health. The idea of when something big happens that shakes you up, you’re sent into a spiral. The one person that you knew for sure loved you, suddenly wants to break up. The illogical part of your brain is “Oh she doesn’t love me.” That’s not true, but that’s what you hear. “Well if she doesn’t love me, no one loves me.” “Why would they love me?” That’s all that mental anguish and all of the things the devil on your shoulder whispers in your ear. So, then you start to think, “Maybe no one loves me.” “Maybe I don’t need to be here.” I think part of the book is trying to quiet the voice that tears down everything. These self-defeating thoughts that one has, they’re not logical. They’re not born from an individual outside yourself. They’re born from yourself, they’re born from you. These are the things you’re saying about yourself. “No one loves me, might as well disappear in the woods, I don’t need anyone.” But that’s also the voice of grief, the voice of hurt. It’s trying to understand that voice. I love memoirs that talk about the vulnerabilities of that voice and share it with others because then other people can be like “Yeah, I felt that way too.” There’s such a stigma attached to someone saying these things. For someone to voice their hurt. I think the reason why I write memoirs is that I’m trying to find people. So, I can say it’s not that lonely. These things are a way to connect us. It sucks. A breakup sucks. You’re allowed to feel whatever you’re going to have to feel, but you’re not by yourself. You may feel like it right now, and it’s okay to feel like it right now. But eventually, you’re gonna find that there are people around you.

Natasha: When you’re going through those emotions, do you think that writers need to wait and evolve to write down how they feel successfully? Like if no one else understands your work but you, maybe you’re not ready to tell the story. Do writers need to wait until they’re ready?

Ira: So, this book is different from any other book I’ve written. In my nonfiction classes, I always talk about this idea of emotional distance. Having the emotional distance to write about a certain event. I think the reason we turn to memoirs is that we like to see the dance between the double “I". The writer at the desk versus the character in the moment. We like to see that dance. With this book, I think I understand writers who have gone through trauma. When you go through something that shakes you up so much, you can’t think of anything else to write about! I was working on a book about being a monk in Thailand. But as soon as the breakup happened, I’m like “Psh! I’m not in a monk place right now! I can’t write this!” I’m having this crisis and this is the only thing I can think about. When I first wrote this book, I wasn’t writing it to share it. I think the writing process and publishing process are two completely different things. This was solely written with the door closed. With not having a thought that it’s going to go anywhere. I just had to figure shit out, ha! Writing to me has been my only way to access that. I do things in my writing that I don’t do when I’m speaking to my friends. There’s something freeing about it. If you thought of the first draft as a book, it was a terrible book! It was 120 pages of me trying to get it out and figure stuff out. I think the fragments of time came with revision. You have to go back and see if this will go out into a larger world. You really have to think about that. It’s not about you anymore. That being said, don’t censor yourself. If you feel like you have something you need to write about and you don’t have the distance, just write about it! But don’t show us. If you’re not comfortable showing then don’t show, but don’t stop it. So, I do think time is important in that revision process for sure. Time is important when you start thinking about it as a book.

Kail: What was the length of time between when you wrote that first draft in comparison to how long you set it aside? When did you reach into the contemplation of publishing it?

Ira: It took about another year before I decided to give it a go. A lot of things happened in that year. I was feeling a bit better about myself, I had been in a steady relationship, and feeling good. In many ways, when I started feeling good about life again, it was easy to start feeling good about writing this in a fuller way. And then it took another three or four years of just revising! It started off as a 120-page diary aha, a tell-all if you will. Then it grew to like 370, and then it shrunk again, and then it grew again. That’s the thing about writing fragments, you can always add things. But then you have to think about if you really need it.

Natasha: Okay, so final question!

Ira: Go for it!

Natasha: The publishing industry has very slowly evolved, but it’s mostly dominated by cis-straight white men who are in positions to decide what can and cannot be published. What advice do you have for writers navigating this field?

Ira: I think for me, I love the fact that we live in a socially conscious world. There are groups that have never existed before. There are groups that are actively looking for voices that are struggling to be heard. They’re pointing a finger at traditional publishing. But change in the publishing industry is not happening overnight. It’s slow. One of the rejections for this book from a big New York press was that “I can’t sell chick lit written by a dude.” But that’s operating exactly from a very limited close-minded world of what people want. I’ve had writers who have said in many ways, “Well we can’t publish your book because we just published another minority writer already.” When we talk about literary representation, there’s this kind of idea that if one person has written a story then that one story becomes a stand-in. But I think we live in a culture that is beginning to push up against that. Also, we live in a culture that is looking beyond the commercial presses. The reason this book ended up with the University of Nebraska Press is that I love this American Live Series. I love their memoir series. Right from the very beginning, they were publishing writers who were taking risks, who were not writing the traditional story. Writers from different backgrounds, doing different things. I think there’s a rise in wonderful presses that are taking risks. But these things with traditional publishing aren’t going to change overnight. I’m always telling my students, “Yeah, you have to write, but you have to play an active role in what is being read and how it’s being read.” Sure, you can write, but they may not read your work because of the world we live in. So, what are you gonna do? Always think about that. Your job is not only to write but to evolve writing, to evolve reading, and think about other ways words can affect.

Artist Feature

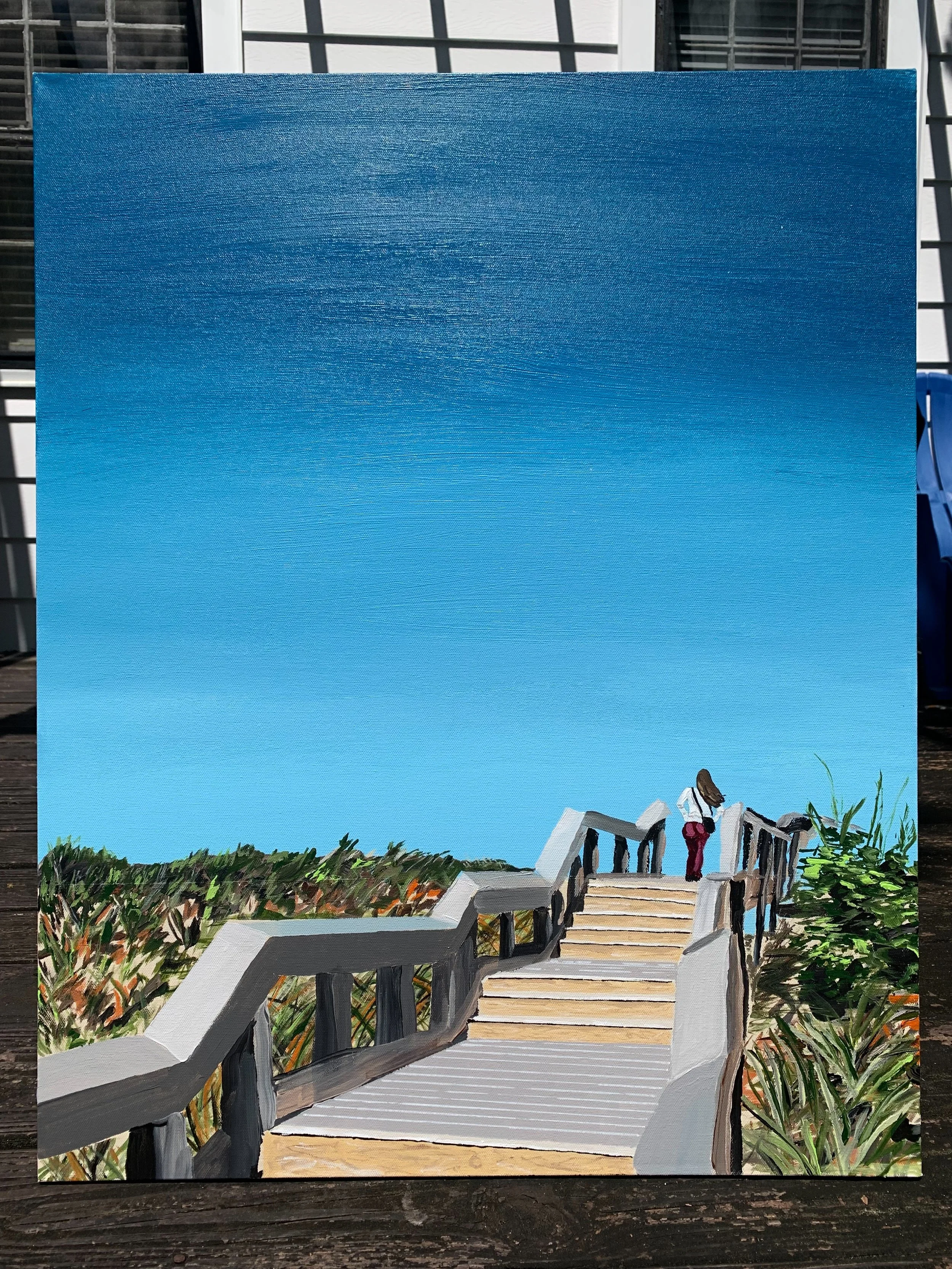

Luc Napier

Where Do We Go From Here

2022, Acrylic on Canvas

Where Do We Go From Here is a painting that resonates with the complexity of human relationships. Napier’s use of depth, emphasizes the uncertainty of what lies beyond the hill. The steps of the pier provoke the hardship that plagues all human beings, uncertainty. Napier has previously commented on the portrait and stated that his motivation behind the painting was, “after a hard conversation.” His use of the color blue and the distance of the painting’s human subject exemplifies the complexity of change and growth. Furthermore, Napier has also conveyed that there’s a possibility that what lies beyond the hill may not, “make sense or mean anything.” The idea that the aftermath may not be as rewarding as we hoped, reveals an honest representation of forgiveness. The fear of uncertainty forever lurks behind forgiveness. Human beings, who have not yet experienced a life that has forgiven the past, are plagued with the fear of uncertainty. The ambiguity of a life that has endured conflict, now must reconcile with the desire to choose forgiveness. Where Do We Go From Here illuminates an individual’s willingness to go over the hill and seek out the next step, despite the uncomfortable nature of the unknown. - Natasha Kane

Talon Announcement

“April was our last month for submissions. We are so grateful to all of the artists who submitted their work to us. Please look forward to our spring issue coming out in mid-may”

Meet Our Featured Creators

About the Author

Ira Sukrungruang was born in Chicago to Thai immigrants. He earned his BA in English from Southern Illinois University Carbondale, and his MFA from The Ohio State University. He is the author of four nonfiction books This Jade World (2021), Buddha’s Dog & Other Meditations (2018), Southside Buddhist (2014) and Talk Thai: The Adventures of Buddhist Boy (2010), the short story collection The Melting Season (2016), and the poetry collection In Thailand It Is Night (2013). With friend Donna Jarrell, he co-edited two anthologies that examines the fat experience through a literary lens—What Are You Looking At? The First Fat Fiction Anthology (2003) and Scoot Over, Skinny: The Fat Nonfiction Anthology (2005). He is a former member of the Board of Trustees for the Association of Writers and Writing Program (AWP), and is currently on the Advisory Board of Machete, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press dedicated to publishing innovative nonfiction by authors who have been historically marginalized.

Sukrungruang is the recipient of the 2015 American Book Award for Southside Buddhist, a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship in Nonfiction Literature, an Arts and Letters Fellowship, and the Anita Claire Scharf Award in Poetry. His work has appeared in many literary journals, including The Rumpus, American Poetry Review, The Sun, and Creative Nonfiction. He is the president of Sweet: A Literary Confection, a literary nonprofit organization, and is the Richard L. Thomas Professor of Creative Writing at Kenyon College.

About the Artist

Luc Napier

A songwriter and painter from central Florida. He likes the color blue,

loud synthesizers, good drums, and the New York Mets. His favorite

flower is the Oakleaf Hydrangea.