THE CATCH NEWSLETTER

Winter 2025 - 2026

Introduction

Our "catch of the month" for the Winter Issue is the Arctic Char. Especially during the colder seasons, this fish represents resilience, survival, and connection. A successful catch is typically shared with the community as a way to unite everyone through their joint effort and diligence. In a similar spirit, I would love to acknowledge all the arduous work everyone put in for the first issue of The Talon this semester! This edition of The Catch features works by Autumn Hill, a local writer here from Jax, and a review of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk, a mellow read for this closing winter season.

– Chloe Pancho

Local Artist Feature: In the Wake of Small Death.

Autumn Hill is a local Jacksonville poet who attended Lavilla and Douglas Anderson School’s of Art for Creative Writing. She has been awarded by multiple organizations including the Arts of life foundation and has had her work exhibited in the Yellow House Museum. She regularly attends open mics to connect with other poets, and believes writing is a bridge for community.

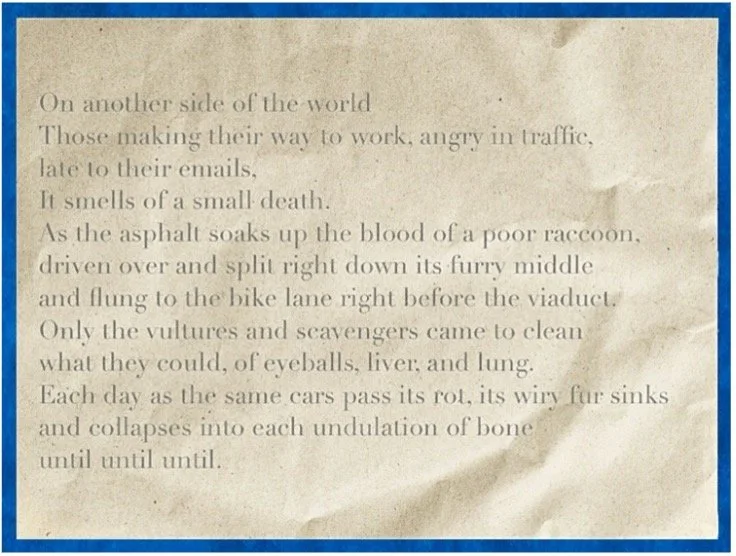

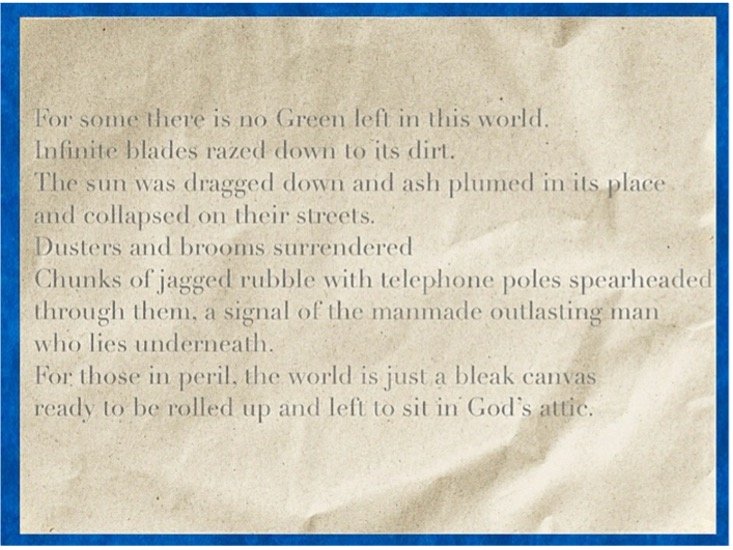

Hill: This is a poem loosely inspired by Guernica by Pablo Picasso and a raccoon I passed everyday on my way to work. In this poem, I tried to study the stark realities of different communities and individuals around the world, and the fragments of sorrow witnessed by each of us.

—

The Catch: What drew you to juxtapose such large-scale devastation with the intimate, mundane image of the raccoon's death? How did you decide that those two images belonged in the same poem?

Hill: Guernica served as the initial inspiration and thematic foundation for this piece, but I still felt I needed solid images to ground it. Everyday leaving my house, I passed this raccoon slain on the roadside, as I have seen many animals before, but the routine of passing its body every day, slowly witnessing its decay felt like a thread I could connect to the horrors we are all witnessing in the news and on social media recently. The raccoon represented to me a local focal point of transformation that usually feels so far way until it is right at your doorstep.

The Catch: You mentioned Pablo Picasso's Guernica being an inspiration for this piece. Were there aspects of this particular painting that stood out to you the most during the writing process?

Hill: Guernica, I knew to be a larger-than-life painting, one that people often described as striking, and something pulled me to it recently, and I dived into the research. Pablo Picasso described himself as apolitical, but when the bombing of Guernica, Spain occurred he felt compelled to channel the horror onto a canvas as a snapshot of human suffering. The simplistic newspaper-like black and white that looks like a bright light about to descend upon the crooked limbs. The harsh faces and tears, the bull making direct eye contact with the viewer, there is just so much packed into the piece versus the wailing dove. I could go on forever.

The Catch: Were there any memorable internal questions or tensions present for you? Whether it be about where to take the thematic elements, perspective shifts, or any other major narrative or emotional component.

Hill: I originally planned to lengthen the poem but there was something final in being so straightforward with the language and having the images speak for themselves. I saw the dual stanzas as a reflection of each other, the first served as the view being reflected into the incident of a raccoon being ran over. I didn’t want it to have a doomsday effect or take such an event lightly, so I attempted to keep it less about my feelings and emotions and rather focused on what was/is true.

The Catch: Your poem touches on the concept of reoccurrence, seen in the images of the cars and the birds. Are there any overarching elements in this piece that you find yourself writing about a lot or revisiting frequently in your work? And if so, why do you think that is?

Hill: Man vs Nature is often something I contemplate in my writing. Our divisiveness when it comes to the world we come from our constant need to separate ourselves from our animalistic instincts by creating a separate reality to quell this anxiety. It is such an interesting concept to try to understand society and even myself, which is why I juxtaposed the destruction of our creations aided by Mother Nature and then Nature being destroyed by our creations, cars vs animal life.

The Catch: The poem concludes with a repeated, "until, until, until." Was there any particular feeling or notion you wanted the reader to leave with that specific ending line?

Hill: The poem was not written as a cautionary tale, but that ultimately came through as the piece unfolded. “Until” to me conveys an unknown deadline, that we could all be in the waiting room of something unimaginable. I left that as the last line to leave the thread hanging. In Guernica there is an ambiguity that I admired, and the construction of the abstracted figures supported that and makes you feel as if they could be anybody. “Until until until” is meant to reflect that abstraction and caution seen in the paintings jagged edges and black and white.

The Stars Know:

The Quiet Rebellion of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead.

Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead follows one of the most endearing, and quietly radical, protagonists I’ve had the privilege of encountering in a contemporary novel. Set in a remote Polish village, the story centers on Janina, an eccentric, sharp-witted elderly woman whose life becomes entangled with a string of mysterious deaths in her community. What could easily have been a straightforward murder mystery becomes something far more textured and stranger in Tokarczuk’s hands.

The novel radiates a quiet charm. Even as bodies begin to appear, there’s a pervasive sense of solitude, a kind of stillness that softens the edges of the violence. Tokarczuk lingers on details others might rush past: long passages exploring translations of French poet Blake’s work, or Janina’s slow, affectionate cataloging of each house and the peculiar people who inhabit them. These moments might seem meandering on the surface, but they reveal the richness of Janina’s inner world. Her perspective is so distinct, so insistently her own, that even the most mundane observations feel newly illuminated.

Janina’s quirks aren’t just for mere decoration though. She interprets every event through astrology, convinced that the stars shape human behavior with absolute precision. She speaks of animals with a reverence that borders on spiritual, believing she shares a real, almost physical bond with the creatures that roam the surrounding forests. She is undeniably odd, but Tokarczuk refuses to flatten her into the familiar “quirky old woman” archetype. Instead, Janina becomes a vessel for the novel’s shifting tones, part philosophical meditation, part ecological fable, and part crime story

That genre fluidity is one of the book’s greatest strengths. Tokarczuk moves effortlessly between moods, bleakness, humor, melancholy, suspense, without ever losing the thread of Janina’s voice. The result is a novel that feels both grounded and otherworldly, intimate yet expansive. Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead is not just your average whodunit mystery. It’s a character study, a moral inquiry, and a quiet rebellion against the ways society dismisses certain kinds of people. And after all these shifts and reveals, Janina remains its beating heart, strange and brilliant, a presence that lingers long after the final page.